Of the opinions of man, they are certainly without end. And all that holds them in their diversity think they are correct.

Over the last seven years, I’ve been trying my best to understand better what it means to be human and how to better practice a fuller and healthier life. Over that time, I have made many changes in my course based on continued self-evaluation and continual self-education along the way. My journey through a perpetual refining fire, if you will. Not of whim but of further refinement as I continue to learn and observe the effects of the modifications to my lifestyle and dietary practices along the way.

Today, I am in a place where I have embraced the idea that the best answers are usually found somewhere in the middle, away from the extremes.

When I first started this journey, I was determined to find myself in a much healthier place through an individual practice of recovery. I love that word…Recovery. The idea of changing my covering, the physical shelter of my consciousness, will, and spirit, if you will. That is exactly what I was doing and will continue to do.

Today, the physical practices that make up my journey consist of three distinct pillars. Quality sleep, healthy diet, and consistent daily exercise. Some might argue there is more, but for me, these are the macros of my current state of physical being. If I allow any one of these to suffer, the others follow.

In time, and in another post, I will expand further on all of these three, but today I want to focus on what I currently believe is likely the best way to approach nutrition(diet).

TL;DR: A Mediterranian Diet is likely the best solution.

What follows are my findings regarding human physiology and why I believe a Mediterranian Diet is likely the best solution to live a fuller and more lively healthspan rather than one of the current popular extremes found in veganism or diets that focus on consuming larger amounts of animal-based foods(Keto or Carnivore), based solely on physiological features and attributes.

Human physiology is significantly different from that of a true herbivore, and these differences reflect the omnivorous nature of humans. Here are some key differences:

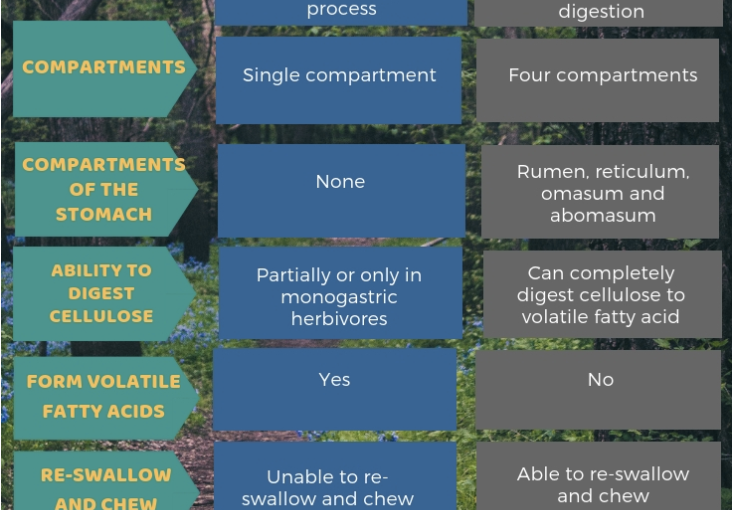

- Digestive Tract: Herbivores have a longer digestive tract compared to humans. This is because plant material, especially cellulose, is more difficult to break down and requires more time to process. The longer digestive tract in herbivores allows for more efficient absorption of nutrients. In contrast, humans have a relatively shorter digestive tract suited to the digestion of both plant and animal matter.

- Stomach Acidity: Humans have a more acidic stomach compared to herbivores. The pH level in a human stomach is typically around 1.5 to 3.5, ideal for breaking down animal protein and killing potential pathogens found in meat. On the other hand, the stomach of a herbivore is usually less acidic, as it needs to support the growth of bacteria that help break down cellulose from plants.

- Teeth Structure: Herbivores have teeth designed for grinding plant material. For example, cows have large molars for grinding grass, and beavers have sharp incisors to cut through wood. Humans, however, have a variety of teeth, including incisors for biting, canines for tearing, and molars for grinding, reflecting our omnivorous diet.

- Enzymes: Herbivores produce certain enzymes that humans do not. For instance, they can produce cellulase, an enzyme needed to break down cellulose in plant cell walls. Humans, on the other hand, lack the ability to produce this enzyme, so we can’t fully digest raw plant material.

- Cecum: The cecum, a pouch at the beginning of the large intestine, plays a significant role in the digestion of plant material in many herbivores, hosting a large number of bacteria that break down cellulose. Humans have a small, functionally insignificant cecum. In fact, the human appendix is a vestigial cecum.

- Energy Utilization: Herbivores, especially ruminants like cows, utilize fermentation to break down plant matter, releasing gases in the process. This slower digestion process enables maximum extraction of nutrients from plant materials. Humans, on the other hand, digest food much more quickly, which is suited to the quick energy release needed for our high-metabolism brains and bodies.

These are general differences, and there are many variations among different species of herbivores, but overall, these points highlight some of the fundamental physiological distinctions between humans and true herbivores. But just as with herbivores, human physiology differs in several ways from that of true carnivores. Here are some notable differences:

- Digestive Tract: True carnivores tend to have shorter digestive tracts compared to humans. This is because meat can be broken down and absorbed relatively quickly and doesn’t require the longer transit time needed for plant material. The shorter digestive tract also helps to pass potentially harmful bacteria present in meat quickly.

- Stomach Acidity: Carnivores have a highly acidic stomach, more so than humans, to quickly break down proteins found in meat and kill bacteria that may be present in their food. While the human stomach is also acidic (with a pH of around 1.5 to 3.5), it is not as consistently strong as that of a carnivore.

- Teeth Structure: Carnivores have a dental structure designed for a meat-based diet. They have sharp, pointed teeth for tearing flesh and strong jaws to crush bone. Humans, in contrast, have a mixed set of teeth (incisors, canines, premolars, and molars) suitable for an omnivorous diet, including both plant and animal matter.

- Enzymes: Humans produce a variety of digestive enzymes to break down a mix of macronutrients (proteins, fats, and carbohydrates). Carnivores, on the other hand, primarily produce enzymes like proteases and lipases, which are needed to digest protein and fat.

- Vitamin Production: Some carnivores, like cats, can synthesize certain nutrients that humans cannot. For example, cats can produce taurine, an essential amino acid, and vitamin A from precursors, while humans must obtain these nutrients directly from their diet.

- Cecum and Colon: Carnivores typically have a small cecum and colon because these parts of the digestive tract are primarily involved in breaking down plant matter. Humans, on the other hand, have a larger colon that allows for the fermentation of plant material and the absorption of water and certain vitamins produced by gut bacteria.

- Dietary Cholesterol and Saturated Fat: Humans are more susceptible to high levels of dietary cholesterol and saturated fat, which can contribute to heart disease. In contrast, many carnivores can consume large amounts of these substances without the same health risks.

Caveat: It is crucial to remember that dietary cholesterol does not affect blood cholesterol levels as much as once thought. Your liver produces more cholesterol when you eat a diet high in sugar and refined carbohydrates.

I personally suspect that if there are any problems related to the consumption of dietary cholesterol, it is found in the nutrient density and digestive availability of animal fats, much like refined carbohydrates and added sugars.

While these are general differences, it’s important to remember that there are many variations among different species of carnivores. These points highlight some of the key physiological distinctions between humans and true carnivores.

An omnivorous diet reflects the evolution of human gastrointestinal physiology and our dietary flexibility that has contributed to our survival and success as a species. This means humans are equipped to eat and process a wide range of foods, both plant and animal-based. Here are some reasons why the omnivore framework best fits our understanding of human gastrointestinal physiology:

- Diversity of Teeth: Humans have a variety of tooth types (incisors, canines, premolars, and molars), which reflects an omnivorous diet. Incisors and canines are designed for biting and tearing food (typical of carnivores), while our molars and premolars are flat and suited for grinding plant material (typical of herbivores).

- Digestive Enzymes: Humans produce a range of digestive enzymes that allow us to break down a variety of nutrients. For example, amylase, produced in our saliva, helps to break down carbohydrates, while proteases and lipases in our stomach and small intestine aid in the digestion of proteins and fats.

- Digestive Tract Length: Our digestive tract length is intermediate, not as long as in most herbivores, which need extensive time and space to break down cellulose, and not as short as in carnivores, which need to quickly process and expel meat to avoid harmful bacterial growth.

- Stomach Acidity: The acidity of our stomachs is capable of breaking down both plant and animal foods and can effectively kill many of the harmful bacteria found in meat.

- Dietary Requirements: Humans require a mix of nutrients, some of which are more readily available in animal foods (like vitamin B12 and preformed vitamin A) and others that are more abundant in plant foods (like vitamin C and dietary fiber).

- Evolutionary Evidence: From an evolutionary perspective, the ability to consume a mixed diet has likely been a key factor in human survival. Being able to eat a wide range of foods made us more adaptable to different environments and less dependent on a single food source.

- Metabolic Adaptability: Humans are metabolically flexible and able to shift our metabolism to use fats, proteins, or carbohydrates for energy depending on dietary intake and energy needs. This adaptability supports an omnivorous diet.

- Cultural and Social Factors: Humans across cultures and throughout history have consumed a diverse range of foods. This reflects not only our physiological adaptability but also our social and cultural practices around food, which often include both plant and animal sources.

Therefore, understanding humans as omnivores helps us appreciate the complexity and flexibility of our dietary needs and digestion. It recognizes our evolutionary history and cultural practices related to food over many thousands of years of evolution and adaptation.