PREFACE

The original “Glutton or Epicure” has been completely revised and much enlarged, including considerable new matter added in the form of testimony by competent investigators, which confirms the original claims of the book and supplements them with important suggestions.

The “New Glutton or Epicure” is now issued as a companion volume to the “A.B.-Z. of Our Own Nutrition,” in the “A. B. C. Series,” and is intended to broaden the illustration of the necessity of dietetic economy in the pursuit of an easy way to successful living, in a manner calculated to appeal to a variety of readers; and wherein it may suggest the scrappiness and extravagance of an intemperate screed, the author joins in the criticism of the purists and offers in apology the excuse that so-called screeds sometimes attract attention where more sober statement fails to be heard.

Especial attention is invited to the “Explanation of the A.B.C. Series,” at the back of this volume, as showing the desirability of regard for environment in all its phases; and also to the section, “Tell-tale Excreta,” on page 142, an evidence of right or faulty feeding persistently neglected heretofore, but of utmost importance in a broad study of the nutrition problem.

The professional approval of Drs. Van Someren, Higgins, Kellogg, and Dewey, representing wide differences of points of view and opportunity of application, are most valuable contributions to the subject. The confirmation of high physiological authority strengthens this professional endorsement. The testimony of lay colleagues given is equally valuable and comes from widely separated experiences, and from observers whose evidence carries great weight. The commandante of a battleship cruising in foreign waters and representing the national descent of Luigi Cornaro; a general manager of one of the largest insurance companies of the world; a cosmopolitan artist of American farm birth and French matrimonial choice and residence; and a distinguished bon vivant, each with a world of experience, testifying in their own manner of expression, is appreciated as most valuable assistance to the cause of economic dietetic reform.

During the original experiments in Chicago, and in Dayton, Ohio, the originator was much indebted to James H. Lacey, Esquire, of New Orleans, La., and Cedar Rapids, for helpful suggestions, which his early training as a pharmaceutical chemist rendered him able to give.

There are also numerous altruistic, self-sacrificing women, who have been active colleagues of the author in testing the virtues of an economic nutrition, and who have greatly assisted in making the economy an added new pleasure of life, instead of being a restraint or a deprivation. This is accomplished easily by a change of attitude towards the question, and in such reform women must have an important part to play. To their kindly meant, but hygienically unwise, aggressive hospitality, in begging friends to eat and drink more than they want, just to satisfy their own generous impulses, is due much of the milder gluttony that is prevalent.

Imposition upon the body of any excess of food or drink is one of the most dangerous and far-reaching of self-abuses; because whatever the body has no need of at the moment must be gotten rid of at the expense of much valuable energy taken away from brain-service. Hence it is that when there is intestinal constipation the energy-reserve is lowered enormously, and even where there is no painful obstruction, the mere passage of waste through some twenty to twenty-five feet of convoluted intestinal canal is a great tax upon available mental and physical power; and this disability is often imposed on innocent men by well-meaning women in the exercise of a too aggressive hospitality.

Mention of constipation suggests another reference to one of the specially new features of this discussion, insisted upon by a truly economic and æsthetic nutrition, and herein lifted out of the depths of a morbid prejudice to testify to the necessity of care in the manner of taking food for the maintenance of a respectable self-respect. So firmly rooted is the fallacy that a daily generous defecation is necessary to health that less frequent periodicity is looked upon with alarm, whereas a normally economic nutrition is proven by greater infrequency, accompanied by an entire absence of difficulty in defecating and by escape from the usual putridity due to the necessity of bacterial decomposition.

To illustrate the prevailing ignorance relative to this most important necessity of self-care, and also a traditional prejudice, even among physicians, the following extract from a letter just received is given: “You ask me to define more exactly what I mean by constipation; this is not at all difficult; I mean skipping a day in having a call to stool. There was no trouble about it, and the quantity was not large, but when I mentioned it to my doctor he advised me to stop chewing if it interfered with the regular daily stools. I must confess that I never felt so well as while I was chewing and sipping, instead of the hasty bolting and gulping which one is apt to do on thoughtless or busy occasions, but I don’t think it is worth while for a chap to monkey with his hygienic department when he is employing a professional regularly to tell him the latest kink about health.” To this surprising state of … the evidence of “professionals” like Van Someren, Kellogg, Higgins, and Dewey, as well as that of the great men of physiology who have spoken herein, and in the “A.B.-Z. of Our Own Nutrition,” gives hopeful answer, but suggests a warning.

The author has noticed that immediately folk begin to give attention to any new régime relative to diet, exercise, mental discipline, or whatever else, they begin to charge all unusual happenings to the change of habit, whereas before the same things were common but unnoticed. Even among men of scientific habit of thought, unduly constipated by stale conservatism, the old, old corpse of tradition, “The accumulated experience of the whole race must be correct,” is revived and used in argument contentiously; but to this relapse into non-scientific reasoning comes the reply: “If the accumulated experience of the human race is evidence that crime and disease are natural, then disease and crime are good things and should not be discouraged.”

There are many sorts of constipation, the worst of which are constipation of affection, of appreciation, of gratitude, and of all the constructive virtues which constitute true altruism. Let us avoid sinning in this regard! In pursuit of this thought the following is àpropos:

SPECIAL RECOGNITION

The author wishes here, also, to express gratitude to many who have not figured by name in the “A.B.-Z.,” or elsewhere herein, but whose assistance, encouragement, criticism, and example have helped the cause along in one way or another. Of these many friends a few are quickly recalled, but not necessarily in the order of their friendly service. To John H. Patterson, Esquire, of Dayton, Ohio; Col. James F. O’Shaughnessy, of New York; Stewart Chisholm, Esquire, of Cleveland, Ohio; Fred E. Wadsworth, Esquire, of Detroit, Michigan; and Henry C. Butcher, Esquire, of Philadelphia, are due much for encouragement in pursuing the investigation at critical moments of the struggle; as well as to Hon. William J. Van Patten, of Burlington, Vermont, whose interest in the “A.B.C. Series” began with “Menticulture” and has continued unabated. In Dr. Swan M. Burnett, of Washington, D. C., has been enjoyed a mentor with great scientific discrimination and a sympathy in the refinements of art and sentiment, as expressed in Japanese æsthetic civilization, which has been extremely encouraging and most inspiring in relation to the whole A.B.C. idea.

From Gervais Kerr, Esquire, of Venice, came one of the important suggestions incorporated in the A.B.-Z. Primer; and the young Venetian artist, E. C. Leon Boehm, rendered great service in studying habits of dietetics among the peoples of the Balkan Peninsular, in Turkey, along the Dalmatian Coast, and in Croatia.

Prof. William James, of Harvard University, in his Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburg, Scotland, published under the title of “The Varieties of Religious Experience,” gave the practical reformatory effort of the “A.B.C. Series” a great impetus by quoting approvingly from “Menticulture” and “Happiness.” Coming from a teacher of philosophy and psychology, with a physiological training and an M.D. degree to support the approval, recognition is much appreciated; but, in addition to his published utterances, Dr. James has followed the psycho-physiological studies of the movement with interest, and has given much valued encouragement.

This does not begin to complete the list of those to whom the author owes a debt of especial gratitude. The argus-eyed vigilance of the collectors and doctors of world-news, who mould public opinion in a great measure, has brought to the cause of dietetic reform established upon an æsthetic basis their kindly assistance, but, as usual, they prefer to remain incog. In this seclusion, however, Ralph D. Blumenfeld, Esquire, of London, and Roswell Martin Field, Esquire, of Chicago, cannot be included; neither can Charles Jay Taylor, the originator of the Taylor-Maid girl. James P. Reilly, Esquire, of New York, has lightened the labours of the investigator, and has strengthened his arm in many ways; as have also Messrs. B. F. Stevens and Brown, of London, not alone as most efficient agents, but as friends interested in the cause in hand. In the various books of the series opportunity has occurred to express appreciation of many sympathetic friendships, and in heart and memory they hold perpetual carnival. To Major Thomas E. Davis, of the New Orleans Picayune, is due more than mere expression of gratitude for excellent editorials on our subject; and across the ocean, Sir Thomas Barlow, the private physician of King Edward VII, Dr. Leonard Huxley, Prof. Alfred Marshall, of Cambridge University, and Reginald Barratt, Esquire, of London, have been most sympathetic and assistful. On both sides of the waters, William Dana Orcutt, Esquire, of The University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Frederick A. Stokes, Esquire, of New York, have added friendship for the cause to much appreciated practical assistance.

These and many others are preferred-creditors of gratitude, in addition to those whose mention is embodied elsewhere in the various books of the “Series.”

As attempted to be shown in the “A.B.-Z.,” under the caption “Bunching Hits and Personal Umpiring,” this study of menticulture from the basis of economic and epicurean nutrition, in connection with a purified exterior and interior environment, is “team-work,” as in football, cricket, or base-ball, and a laudable enthusiasm is an important feature of the game; hence, to conclude, this especial book, being a personal confession, relaxation, effusion, expansion, as it were, of the practical benefits of economic body nutrition and menti-nutrition, it seems the appropriate place to offer personal tribute outside and inside the intimate family relations, as freely as menticultural impulse may suggest.

HORACE FLETCHER.

PREFACE TO 1906 EDITIONS

Since the former introductions were written much success has been attained in further advancing the reforms advocated in the A. B. C. Life Series. Professor Chittenden has published his report on the Yale experiments in book form in both America[1] and England,[2] and his results have been accepted in scientific circles the world over as authoritatively conclusive.

At the present writing the most important Health Boards of Europe[3] are planning to put the new standards of dietary economy into practical use among public charges in a manner that can only result in benefit to the wards of the nations as well as make an important saving to the taxpayers. In the most important of these foreign public health departments the Health Officer of the Board has himself practised the newly established economy for two years, and his plans are formulated on personal experience which fully confirms Professor Chittenden’s report and that of the author as herein related.

At a missionary agricultural college, situated near Nashville, Tenn., where the students earn their tuition and their board while pursuing their studies, a six months’ test of what is termed “Fletcherism” resulted in a saving of about one half of the drafts on the commissary, immunity from illness, increased energy, strength and endurance, and general adoption of the suggestions published in the several books of the author included in the A. B. C. Life Series.

In the various departments and branches of the Battle Creek Sanitarium in America, and widely scattered over the world, some eight hundred employees and thousands of patients have been accumulating evidence of the efficacy of “Fletcherism” for more than three years, and scarce a month passes without a letter from Dr. Kellogg to the author containing new testimony confirming the A. B. C. selections and suggestions.

The author has received within the past two years more than a thousand letters bearing the approval of the writers with report of benefits received which seem almost miraculous, and these include the leaders in many branches of human occupation—physiologists, surgeons, medical practitioners, artists, business men, literary workers, athletes, working men and women, and almost every degree of mental and physical activity.

One of the medical advisers of King Edward, of whom the King once said: “He is a splendid doctor but a poor courtier,” follows the suggestions of these books in prescribing to his sumptuous clients.

THE NEW GLUTTON or EPICURE

It is now five years since the first section of this crude little announcement of a great physiological discovery was published; and while the author has spent all the intervening years in unremitting study of the subject of which it treats, with the heads of many of the great physiological laboratories of the world assisting him with their best facilities and information, as to the “reasons for things,” there is but small correction to make.

This does not imply that the “last word” upon the subject has been herein stated, or that corrections may not be made as the study progresses, but it means, that as an honest description of an effort to get to understand the natural requirements in our own nutrition, it is perhaps better put than the same author could now do; that is, if intended for the enlightenment of persons whose curiosity has not yet been excited, or whose interest in their nutritive welfare is still young and inexperienced.

With regard to the statement that “whatever has no taste is not nutritious,” copied from a high educational authority, correction certainly must be made. Pure proteid has no perceptible taste as measured by taste-bud appreciation, any more than pure water has specific taste, and yet who may not say that “water tastes good” when one is really thirsty. Taste is a very subtle sense and is closely allied to feeling. Things are often said to taste good because they feel good in the mouth or to the throat as they descend to the stomach.

Regarding also the advice to remove from the mouth refractory substance that the teeth and saliva cannot reduce to a condition to excite the Swallowing Impulse. There is theoretical and actual nutriment in the cottony fibre of tough lobster, or poor fish, or lean pork, and there is good reason to believe that a strong digestive apparatus can take care of such tough substance after a fashion and get nutriment out of it. In the same way the hard, woody fibre of old nuts is the identical material that was rich in juicy oils and proteid when the nuts were fresh, but if swallowed in the toughened condition that age brings to nuts, it is but slowly reduced in the stomach and intestines and only at enormous expense. If putrifactive bacterial decomposition has to be resorted to to get rid of the stuff the process is then poisonous as well as difficult.

According to physiological authority which we must, for the moment, accept, proteid is a vitally-necessary material and we cannot afford to waste it. Our life depends upon proteid to replace the waste of muscular tissue which occurs with every movement, but when even good proteid is found by the mouth to be in a form that is too refractory for the teeth to handle, it is poor policy to send it on to the toothless stomach and intestines for the accomplishment of the reduction. If the mouth cannot handle what its guardian senses don’t like, it can spit it out and get rid of it immediately; but if the stomach or intestines are afflicted with something that is harder than they can easily take care of, they have to call in the assistance of bacterial scavengers whose method is poisonous decomposition, and whose fee is putridity of odour penetrating the whole system and issuing at every pore, making Cologne water a large commodity even in so-called Polite Society.

There are discernible in the mouth distinct senses of discrimination against substance that is undesirable for the system. If the mouth senses are permitted to express an opinion, their antipathy is easily read. It is far safer to spit out what the natural impulse of swallowing hesitates at, or fails to suck up with avidity, than it is to force a swallowing to get rid of it simply to satisfy a prudish “table manner” objection. To avoid “impolite” condemnation we really make “hogs of ourselves” “on the sly,” and vulgar slang alone is appropriate to express the shameful confession.

As a matter of fact, if one faithfully practise mouth thoroughness in connection with all his food for a term of a few weeks, he will find that the appetite ceases to invite the sort of things that have to be spit out. The appetite gradually but unfailingly inclines to foods that are profitable all the way through, and in which there is little or no waste. This revelation alone shows a delicate usefulness of Appetite that has escaped students of the human senses.

In the matter of the insalivation of liquids, evidence continues to accumulate to show that in the present prevalence of liquid or soft foods lies the great danger to the digestive economy of man. Through them, mouth work becomes neglected, and the tendency is to force the stomach and intestines to take on the work of the powerful mouth muscles and glands in addition to their own work, and in the straining that ensues trouble begins.

There is now no doubt but that taste is evidence of a chemical process going on that should not be interrupted or transferred to the interior of the body. Tried upon milk for so long a period as seventeen days, during which nothing was taken but milk, not even water, thorough insalivation secured more than a twenty-five per cent economy in actual assimilation; not alone with one subject, but with no less than five persons, living on milk from the same cow, and all of whose strict test history was recorded. It seems also to be the only way in which a practically odourless solid excreta is obtainable, and this is certainly evidence worth considering and a desideratum worth striving for.

While it is an excellent thing to give thorough mouth attention to anything taken into the body, to solids alone, even if liquids are neglected, the best economic and cleanly results are only obtained when all substances, both liquid and solid, are either munched or tasted out of existence, as it were, and have been absorbed into a waiting and willing body; a body with an earned appetite.

With liquids one simply has to do as the wine-tasters and the tea-tasters do. Small sips are intaken and the liquid is tasted between the top of the tongue (the spoon end) and the roof of the mouth until all the taste is tasted out of it, and the Swallowing Impulse has claimed it. This is by no means a disagreeable task, and as soon as the unnaturally acquired habit of greed and impatience is conquered, the reward of following this natural requirement is very great and increases with practice. Five years of experience has taught the author that a really keen appreciation of taste and its delicacy of possible refinement is not known to persons of ordinary habits of life. The pleasure which comes with conformity with the natural requirements is truly Epicurean and disregard of them is as surely gluttonous.

The author still claims discovery of a distinct physiological function which he first named “Nature’s Food Filter.” Van Someren preferred the name of a “New Reflex of Deglutition.” It is, in fact, the “Natural Swallowing Impulse,” invited only by food mechanically and chemically prepared for passing on to the interior, call it by whatever name you like or may.

At the time this little book was first published, the only note in favour of giving special attention to “buccal digestion,” that had been sounded, was the advice of Mr. Gladstone to his children, “Chew your food thirty-two times to each mouthful,” or words to that effect. The “Masticate well” prescription of the physician when given at all, had meant little or nothing, to either the patient or to the prescriber, except that one must not swallow hard food whole.

For two years after its publication little heed was given to the suggestion because the author happened not to be a medical man, but, finally, the reserve of indifference was broken, first by Dr. Joseph Blumfeld, in a review of the book in the London Lancet, and soon after by Dr. Ernest Van Someren of Venice, Italy, an English physician residing and practising in Venice. Dr. Van Someren’s interest and experience are best stated in his own words, as follows:

THE PERSONAL “CASE” AND “ENDORSEMENT” of DR. ERNEST VAN SOMEREN

AN ENGLISH PHYSICIAN AND SURGEON, PRACTICING IN VENICE, ITALY

“My dear Mr. Fletcher:

“It would be almost àpropos to send you, as an endorsement of your principles, the dictum of the ragged and dirty tramp in the advertisement of Pear’s soap. I would have to amend it slightly and say: ‘I used your {principlessoap} three years ago; since when I have used no other.’ I say ‘almost àpropos‘ advisedly, for, while the soap claims to keep the outer man clean, the practice of your principles justly claims to keep the inner man sweet and clean, so lessening the need to cleanse the outer man!

“A well-known English surgeon (I think Sir Wm. Mitchell Banks) recommends physicians and surgeons to take a leaf from the book of patent-medicine vendors, and make their patients testify to their successful treatment. I will take the hint and give you, as my ‘doctor,’ a testimonial of how personally I am benefited by your advice.

“Three years ago, when I first met you, though under thirty years of age, and myself a practising physician and surgeon, I was suffering from gout, and had been under the régime of a London specialist for the treatment of that malady. Though vigorously adhering to the prescribed diet, I suffered from time to time. My symptoms were typical—paroxysmal pain in my right great toe and in the last joints of both little fingers, the right one being tumefied with the well-known ‘node.’ From time to time, generally once a month, I suffered from incapacitating headaches. Frequent colds, boils on the neck and face, chronic eczema of the toes, and frequent acid dyspepsia were other and painful signs that the life I was leading was not a healthy one. Yet I was accounted a healthy person by my friends, and was, withal, athletic. I fenced an hour daily, took calisthenic exercises every morning, forcing myself to do them, and I rowed when I obtained leisure to do so. In spite of this exercise and an inherent love of fresh air, which kept all the windows of my house open throughout the year, I suffered as above. Worse still, I was losing interest in life and in my work.

“In one or two conversations you laid down your simple principles of economic nutrition. You told me that my food ought to be masticated thoroughly, until taste was eliminated, and that (my) liquid nourishment, if taken, ought to be similarly treated. You also told me that, taking food in this way, I might, without fear of consequences, give free rein to my appetite. To shorten my story, I’ll say that in three months after the practice of these principles my symptoms had disappeared. Not only had my interest in my life and work returned, but my whole point of view had changed, and I found a pleasure in both living and working that was a constant surprise to me. For this, my dear Mr. Fletcher, I can never repay you. My only desire has been and is, to try and do for others in my practice what you did for me.

“Now I have since that time had occasional colds, headaches, and gouty pains; but, whereas formerly I could not explain their causes, I can now invariably trace them to carelessness in the buccal digestion of my food, and can soon shake them off. So much for my testimonial. Now for other matters.

“I do not know what may be the extent of the claims you are advancing in regard to the benefits accruing from the practice of your principles. If you, as you in justice may, claim even the widest benefits as surely following the practice of these principles, many will relegate these claims to the limbo where all such ‘panaceas’ are soon forgotten. They will err greatly if they do so. The seemingly simple procedure of insalivating one’s food most carefully is not calculated to impress people with the fact that great permanent benefit follows. The subtlety of the changes that occur is due to the greatly increased action of a vital process, i. e., of the admixture with the food-stuffs of saliva, in such quantities as to alter the chemical reaction of the initial stage of digestion. This initial change causes a consequent change of all the processes following it, and a change also in the final products of the entire process of digestion; the greatest change being, perhaps, the elimination of last-resort digestion by the intestinal flora (digestion by decomposition caused by bacteria), and consequent elimination from the body, of the toxins they produce. The life of an organism has been defined as ‘the sum of all those inter-actions which take place between the various cells constituting the organism and their several environments.’ (Harry Campbell.) The final products of digestion are absorbed into the blood stream, and go to form part of the ‘several environments’ of the cells. The individual cell, the various groups of specialised cells, such as the brain, nerves, muscles, bones, etc., in short, the whole organism is beneficially influenced and made more resistent to disease by the purity of a blood stream that no longer contains the toxins of bacterially digested food.

“The further investigation of your discovery by those competent will, I am confident, result in such a simplification of the rules for a healthy life that the medical profession, at present forced by a lack of knowledge of the vital processes of nutrition to base their treatment on the veriest empiricism, will then be able to teach all and sundry how to live. At present, all we can do is to treat and perchance cure for a time certain symptoms, allowing the patient to return afterwards to a mode of life that is really responsible for his malady. ‘Disease is an abnormal mode of life.’ (Harry Campbell.) The three factors in its causation are:

“(a) Cell structure.

“(b) Internal cell environment.

“(c) External body environment.

“Heredity determines, to a very large extent, our cell structure, and consequently our body structure.

“Sanitary science regulates our external body environment as much as the artificial and noxious habits of so-called civilisation will allow. The mental and physical external body environments have also their effect on the organism.

“Your discovery of simple rules for an Economic Nutrition will control the internal cell environment. In doing this, the predisposition to disease is materially affected. The internal cell environment being free from toxic material, and the cell itself better nourished, the cell’s resistance to disease is increased, the possible source of disease being limited to the external body environment.

“In concluding this endorsement I can promise, to each and all who may intelligently practise the principles of Thorough Buccal-Digestion, a complete knowledge of their body’s food requirements, or, as a patient of mine tersely put it, they will learn the way to ‘run their own machines.’

“Yours ever,

“Ernest van Someren.”

Dr. Van Someren and the author, assisted by Dr. Professor Leonardi, of Venice, as Consulting Physiological-Chemist, and several colleagues, pursued some experiments during the winter of 1900-1901; and Dr. Van Someren read a paper on our work, entitled, “Was Luigi Cornaro Right?”, before the meeting of the British Medical Association the following August.

The paper is too long to reprint here but it will be found in full in another volume, entitled, “The A.B.-Z. of Our Own Nutrition.”

The following “Note” by Dr. Professor, Sir Michael Foster, K.C.B., M.P., F.R.S. etc., is a further link in the chain of development of appreciation of the need of serious attention to the science of human nutrition excited by this initiative. (Dr. Foster is the Permanent Honorary President of the International Congress of Physiologists.)

EXPERIMENTS UPON HUMAN NUTRITION

NOTE BY SIR MICHAEL FOSTER, K.C.B., M.P., F.R.S.

“In 1901 Dr. Ernest Van Someren submitted to the British Medical Association, and afterwards to the Congress of Physiologists at Turin, an account of some experiments initiated by Mr. Horace Fletcher. These experiments went to show that the processes of bodily nutrition are very profoundly affected by the preliminary treatment of the food-stuffs in the mouth and indicated that great advantages follow from the adoption of certain methods in eating. The essentials of these special methods, stated briefly and without regard to certain important theoretical considerations discussed by Dr. Van Someren, consist of a specially prolonged mastication which is necessarily associated with an insalivation of the food-stuffs much more thorough than is obtained with ordinary habits.

“The results brought to light by the preliminary experimental trials went to show that such treatment of the food has a most important effect upon the economy of the body, involving in the first place a very notable reduction in the amount of food—and especially of proteid food—necessary to maintain complete efficiency.

“In the second place this treatment produced, in the experience of its originators, an increase in the subjective and objective well-being of those who practise it, and, as they believe, in their power of resistance to the inroads of disease. These secondary effects may indeed be almost assumed as a corollary of the first mentioned; because there can be little doubt that the ingestion of food—and perhaps especially of proteid food—in excess of what is, under the best conditions, sufficient for maintenance and activity, can only be deleterious to the organism, clogging it with waste products which may at times be of a directly toxic nature.

“In the autumn of 1901 Mr. Fletcher and Dr. Van Someren came to Cambridge with the intention of having the matter more closely inquired into, with the assistance of physiological experts. The matter evoked considerable interest in Cambridge, and observations were made not only upon those more immediately interested, but upon other individuals, some of whom were themselves medical men and trained observers.

“Certain facts were established by these observations, which, however, are to be looked upon as still of a preliminary nature. The adoption of the habit of thorough insalivation of the food was found in a consensus of opinion to have an immediate and very striking effect upon appetite, making this more discriminating, and leading to the choice of a simple dietary and in particular reducing the craving for flesh food. The appetite, too, is beyond all question fully satisfied with a dietary considerably less in amount than with ordinary habits is demanded.

“Numerical data were obtained in several cases, but it is not proposed to deal with these in detail here, as they need the supplementary study which will be shortly referred to.

“In two individuals who pushed the method to its limits it was found that complete bodily efficiency was maintained for some weeks upon a dietary which had a total energy value of less than one-half of that usually taken, and comprised little more than one-third of the proteid consumed by the average man.

“It may be doubted if continued efficiency could be maintained with such low values as these, and very prolonged observations would be necessary to establish the facts. But all subjects of the experiments who applied the principles intelligently agreed in finding a very marked reduction in their needs, and experienced an increase in their sense of well-being and an increase in their working powers.

“One fact fully confirmed by the Cambridge observations consists in the effect of the special habits described upon the waste products of the bowel. These are greatly reduced in amount, as might be expected; but they are also markedly changed in character, becoming odourless and inoffensive, and assuming a condition which suggests that the intestine is in a healthier and more aseptic condition than is the case under ordinary circumstances.

“Although the experiments hitherto made are, as already stated, only preliminary in nature and limited in scope, they establish beyond all question that a full and careful study of the matter is urgently called for.

“For this fuller study the Cambridge laboratories do not possess at present either the necessary equipment or the funds to provide it. For the detailed study of the physical efficiency of a man under varying conditions, elaborate and expensive apparatus is required; and the advantages claimed for the special treatment of the food just discussed can only be fully tested by prolonged and laborious experiments calling for a considerable staff of workers.

“It is of great importance that the mind of the lay public should be disabused of the idea that medical science is possessed of final information concerning questions of nutrition. This is very far indeed from being the case. Human nutrition involves highly complex factors, and the scientific basis for our knowledge of the subject is but small; where questions of diet are concerned, medical teaching, no less than popular practice, is to a great extent based upon empiricism.

“But the scientific and social importance of the question is clearly immense, and it is greatly to be desired that its study should be encouraged.

“M. Foster.

“April 26th, 1902.”

The interest excited in Professor Foster was coincident with that espoused by Dr. Professor Henry Pickering Bowditch, Professor of Physiology of Harvard Medical School, and Dean of American Physiologists. Under the ægis of such encouragement the later developments are not at all surprising.

In order to extend and verify the findings of Dr. F. Gowland Hopkins, of Cambridge University, England, as stated in the preceding note by Professor Foster, Professor Russell H. Chittenden, President of the American Physiological Society, Director of the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University, and one of the leading chemico-physiological authorities of the world, as measured by accepted research work, volunteered to submit the author to further test.

The report of this test is too long for reproduction here. It was first published in the Popular Science Monthly of June 1903, but will be found in full in the “A. B.-Z.” just referred to. The special reference to the author’s case and the quoted report of Dr. William G. Anderson, Director of the Yale Gymnasium which tells the story of efficiency, was as follows:

Extract from an article by Professor Russell H. Chittenden in Popular Science Monthly, June, 1903.

“The writer has had in his laboratory for several months past a gentleman (Horace Fletcher) who has for some five years, in pursuit of a study of the subject of human nutrition, practised a certain degree of abstinence in the taking of food and attained important economy with, as he believes, great gain in bodily and mental vigour and with marked improvement in his general health. Under his new method of living he finds himself possessed of a peculiar fitness for work of all kinds and with freedom from the ordinary fatigue incidental to extra physical exertion. In using the word abstinence possibly a wrong impression is given, for the habits of life now followed have resulted in the disappearance of the ordinary craving for food. In other words, the gentleman in question fully satisfies his appetite, but no longer desires the amount of food consumed by most individuals.

“For a period of thirteen days, in January, he was under observation in the writer’s laboratory, his excretions being analysed daily with a view to ascertaining the exact amount of proteid consumed. The results showed that the average daily amount of proteid metabolised was 41.25 grams, the body-weight (165 pounds) remaining practically constant. Especially noteworthy also was the very complete utilisation of the proteid food during this period of observation. It will be observed here that the daily amount of proteid food taken was less than one half that of the minimum Voit standard, and it should also be mentioned that this apparent deficiency in proteid food was not made good by any large consumption of fats or carbohydrates. Further, there was no restriction in diet. On the contrary, there was perfect freedom of choice, and the instructions given were to follow his usual dietetic habits. Analysis of the excretions showed an output of nitrogen equal to the breaking down of 41.25 grams of proteid per day, as an average, the extremes being 33.06 grams and 47.05 grams of proteid.

“In February, a more thorough series of observations was made, involving a careful analysis of the daily diet, together with analysis of the excreta, so that not alone the proteid consumption might be ascertained, but likewise the total intake of fats and carbohydrates. The diet consumed was quite simple, and consisted merely of a prepared cereal food, milk and maple sugar. This diet was taken twice a day for seven days, and was selected by the subject as giving sufficient variety for his needs and quite in accord with his taste. No attempt was made to conform to any given standard of quantity, but the subject took each day such amounts of the above foods as his appetite craved. Each portion taken, however, was carefully weighed in the laboratory, the chemical composition of the food determined, and the fuel value calculated by the usual methods.

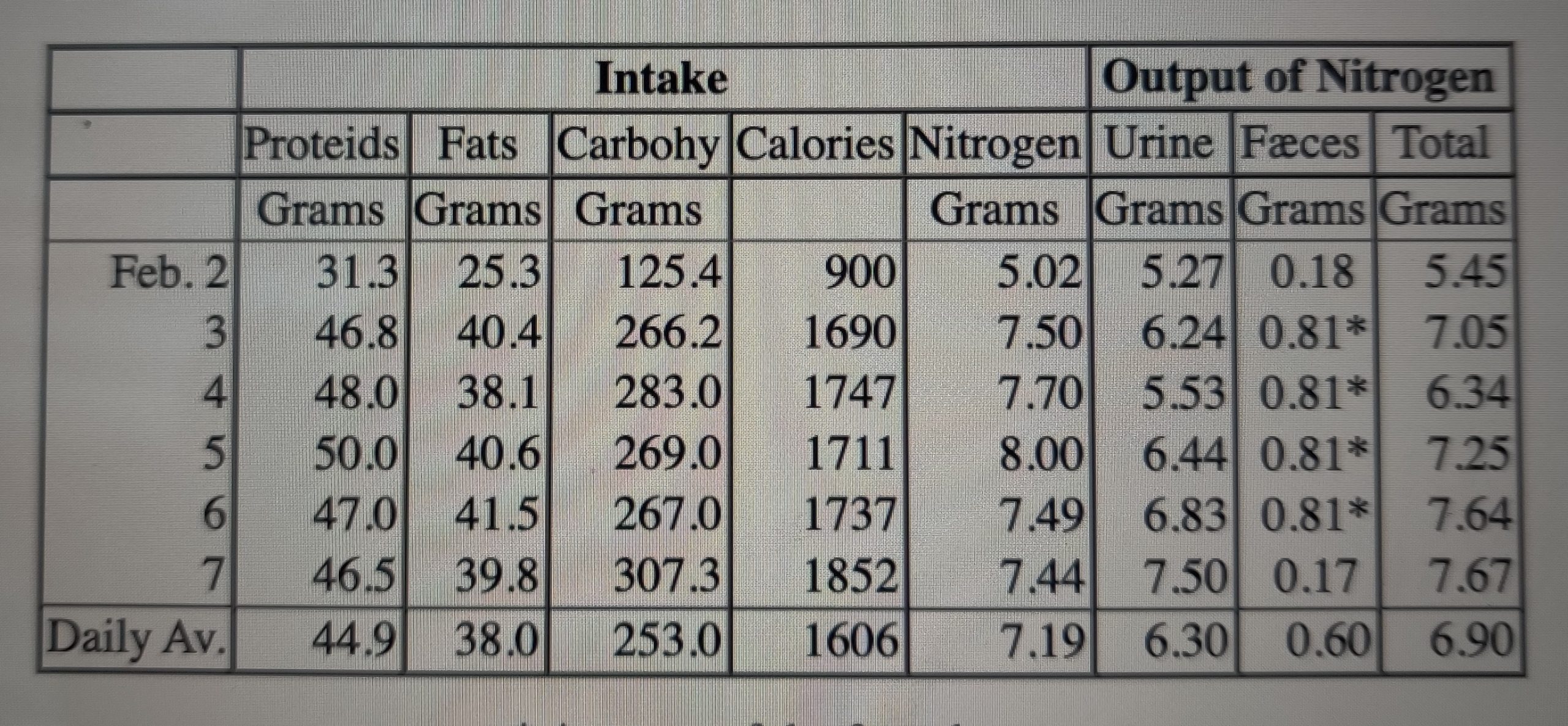

“The following table gives the daily intake of proteids, fats and carbohydrates for six days, together with the calculated fuel value, and also the nitrogen intake, together with the nitrogen output through the excreta. Many other data were obtained showing diminished excretion of uric acid, ethereal sulphates, phosphoric acid, etc., but they need not be discussed here.

* Average of the four days.

“The main things to be noted in these results are, first, that the total daily consumption of proteid amounted on an average to only 45 grams, and that the fat and carbohydrate were taken in quantities only sufficient to bring the total fuel value of the daily food up to a little more than 1,600 large calories. If, however, we eliminate the first day, when for some reason the subject took an unusually small amount of food, these figures are increased somewhat, but they are ridiculously low compared with the ordinarily accepted dietary standards. When we recall that the Voit standard demands at least 118 grams of proteid and a total fuel value of 3,000 large calories daily, we appreciate at once the full significance of the above figures. But it may be asked, was this diet at all adequate for the needs of the body—sufficient for a man weighing 165 pounds? In reply, it may be said that the appetite was satisfied and that the subject had full freedom to take more food if he so desired. To give a physiological answer, it may be said that the body-weight remained practically constant throughout the seven days’ period, and further, it will be observed by comparing the figures of the table that the nitrogen of the intake and the total nitrogen of the output were not far apart. In other words, there was a close approach to what the physiologist calls nitrogenous equilibrium. In fact, it will be noted that on several days the nitrogen output was slightly less than the nitrogen taken in. We are, therefore, apparently justified in saying that the above diet, simple though it was in variety, and in quantity far below the usually accepted requirement, was quite adequate for the needs of the body. In this connection it may be asked, what were the needs of the body during this seven days’ period? This is obviously a very important point. Can a man on such a diet, even though it suffices to keep up body-weight and apparently also physiological equilibrium, do work to any extent? Will there be under such condition a proper degree of fitness for physical work of any kind? In order to ascertain this point, the subject was invited to do physical work at the Yale University Gymnasium and placed under the guidance of the director of the gymnasium, Dr. William G. Anderson. The results of the observations there made, are here given, taken verbatim from Dr. Anderson’s report to the writer.

“‘On the 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th of February, 1903, I gave to Mr. Horace Fletcher the same kind of exercises we give to the Varsity Crew. They are drastic and fatiguing and cannot be done by beginners without soreness and pain resulting. The exercises he was asked to take were of a character to tax the heart and lungs as well as to try the muscles of the limbs and trunk. I should not give these exercises to Freshmen on account of their severity.

“‘Mr. Fletcher has taken these movements with an ease that is unlooked for. He gives evidence of no soreness or lameness and the large groups of muscles respond the second day without evidence of being poisoned by carbon dioxide. There is no evidence of distress after or during the endurance test, i. e., the long run. The heart is fast but regular. It comes back to its normal beat quicker than does the heart of other men of his weight and age.

“‘The case is unusual and I am surprised that Mr. Fletcher can do the work of trained athletes and not give marked evidences of over exertion. As I am in almost constant training I have gone over the same exercises and in about the same way and have given the results for a standard of comparison. (The figures are not given here.)

“‘My conclusion given in condensed form is this. Mr. Fletcher performs this work with greater ease and with fewer noticeable bad results than any man of his age and condition I have ever worked with.’

“To appreciate the full significance of this report, it must be remembered that Mr. Fletcher had for several months past taken practically no exercise other than that involved in daily walks about town.

“In view of the strenuous work imposed during the above four days, it is quite evident that the body had need of a certain amount of nutritive material. Yet the work was done without apparently drawing upon any reserve the body may have possessed. The diet, small though it was, and with only half the accepted requirement in fuel value, still sufficed to furnish the requisite energy. The work was accomplished with perfect ease, without strain, without the usual resultant lameness, without taxing the heart or lungs, and without loss of body-weight. In other words, in Mr. Fletcher’s case at least, the body machinery was kept in perfect fitness without the consumption of any such quantities of fuel as has generally been considered necessary.

“Just here it may be instructive to observe that the food consumed by Mr. Fletcher during this seven days’ period—and which has been shown to be entirely adequate for his bodily needs during strenuous activity—cost eleven cents daily, thus making the total cost for the seven days seventy-seven cents! If we contrast this figure with the amounts generally paid for average nourishment for a like period of time, there is certainly food for serious thought. Mr. Fletcher avers that he has followed his present plan of living for nearly five years; he usually takes two meals a day; has been led to a strong liking for sugar and carbohydrates in general and away from a meat diet; is always in perfect health, and is constantly in a condition of fitness for work. He practises thorough mastication, with more complete insalivation of the food (liquid as well as solid) than is usual, thereby insuring more complete and ready digestion and a more thorough utilisation of the nutritive portions of the food.

“In view of these results, are we not justified in asking ourselves whether we have yet attained a clear comprehension of the real requirements of the body in the matter of daily nutriment? Whether we fully comprehend the best and most economical method of maintaining the body in a state of physiological fitness? The case of Mr. Fletcher just described; the results noted in connection with certain Asiatic peoples; the fruitarians and nutarians in our own country recently studied by Professor Jaffa, of the University of California; all suggest the possibility of much greater physiological economy than we as a race are wont to practise. If these are merely exceptional cases, we need to know it, but if, on the other hand, it is possible for mankind in general to maintain proper nutritive conditions on dietary standards far below those now accepted as necessary, it is time for us to ascertain that fact. For, if our standards are now unnecessarily high, then surely we are not only practising an uneconomical method of sustaining life, but we are subjecting ourselves to conditions the reverse of physiological, and which must of necessity be inimical to our well being. The possibility of more scientific knowledge of the natural requirements of a healthy nutrition is made brighter by the fact that the economic results noted in connection with our metabolism examination of Mr. Fletcher is confirmatory of similar results obtained under the direction and scrutiny of Sir Michael Foster at the University of Cambridge, England, during the autumn and winter of last year; and by Dr. Ernest Van Someren, Mr. Fletcher’s collaborateur, in Venice, on subjects of various ages and of both sexes, some account of which has already been presented to the British Medical Association and to the International Congress of Physiologists at its last meeting at Turin, Italy. At the same time emphasis must be laid upon the fact that no definite and positive conclusions can be arrived at except as the result of careful experiments and observations on many individuals covering long periods of time. This, however, the writer hopes to do in the very near future, with the coöperation of a corps of interested observers.

“The problem is far-reaching. It involves not alone the individual, but society as a whole, for beyond the individual lies the broader field of the community, and what proves helpful for the one will eventually react for the betterment of society and for the improvement of mankind in general.”

This test of work was accomplished on food of the nitrogen value of less than 7 grams daily, whereas the text-books declare that from 16 to 25 grams of nitrogen are necessary to human existence. The heat value of the food consumed during the test, and which was like in amount to what had been habitually taken by the author for about five years previously (less than 1600 large Calories), was only half the amount set down by the majority of the presently-accepted authorities as necessary to run the body of a man of the author’s weight and activity. The heat-economy-showing was verified a week or two later in a 32-hour calorimeter measurement in the apparatus of Professors Atwater and Benedict at Middletown, Conn.

Evidence of even more significant value has accumulated outside the field of the author’s own experiments and tests. After more than a year of careful trial among some thousands of patients and among some hundreds of earnest employees, Dr. James H. Kellogg, of the great Battle Creek Sanitarium, has adopted the suggestions contained in this book as the first requirement of the treatment at the Sanitarium. In like manner, Dr. Edward Hooker Dewey, the sturdy advocate of dietary-economy for the past thirty years, author of the “No-Breakfast” regimen, and various books upon the subject of auto-nutrition and dietary-rest, bent his attention upon the effect of thorough buccal digestion prescribed after a period of rest from outside feeding, and here follows his appreciation as extracted from personal letters.

Before quoting from the high appreciation of Dr. Dewey and Dr. Kellogg it may be well to state that the author stands simply for a test-subject-factor in a commonweal natural inquiry and no praise of the subject attaches to the person of the author. Whatever the author is, in the enjoyment of health and strength, is the result of natural causes which have developed during his study of the natural requirements in our nutrition. Please forget the personal element and consider that what is the author’s gain in efficiency as related, is the possible possession of the reader as well, and whatever work or test the author performs is done as much for the reader as for the author himself.

The several extracts from the letters of Drs. Kellogg and Dewey; the statement relative to an endurance-test made on the author’s fiftieth birthday, on a bicycle in France, volunteered by Edward W. Redfield, last year’s Medal-of-Honorist at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, as well as medalist of last Exposition Universale, Paris; are appreciated and accepted for the subject they endorse; and, as before stated, are entirely impersonal. Instead of using dumb animals for test subjects and getting their unwilling, and sometimes abnormally deranged, participation, the author takes pleasure in submitting to the tests himself, and is thus able to state “symptoms” and “feelings” more accurately, perhaps, than any dog could do. Were vivisection necessary the author would willingly submit to that inconvenience also; but thanks to the skill of a Pawlow, and the ingenuity of a Bowditch coupled with the patience and persistence of a Cannon, as fully related in the “A.B.-Z.,” we not only get the economic results but we are able to know and even see some of the “reasons for things” as well.

Interesting testimony and comment relative to the present study will be found at the end of the volume in communications from Commandante Cesare Agnelli, Clarence F. Low, Esquire, Baron Randolph Natili, and one of unusual suggestiveness, as evidence of the need of further study of nutrition, from Dr. Hubert Higgins of Cambridge, England.

MILITARY-SCIENTIFIC COÖPERATION

With the evidence and interest just outlined, it was not difficult for the author to enlist the coöperation of Surgeon-General O’Reilly of the United States Army and the endorsement of General Leonard Wood for larger investigation of the subject. These officers, both of them surgeons and medical doctors, had supported the militant-martyr-scientist, Dr. Major Walter Reed, in his great sanitary accomplishment; had fought yellow fever to a finish together in Cuba; had traced its spread to a specific cause; and were thereby encouraged to tackle even so common and powerful enemies as Indigestion and Mal-Assimilation.

The investigation now in progress at Yale University, under the direction of Professor Chittenden and under the fostering auspices of the Trustees of the Bache Fund, which is administered by the National Academy of Sciences, and other contributed support, is a Militant-Scientific campaign which will not cease until we know as much about human nutrition, at least, as we know about the nutrition of our domestic animals.

In this little book, however, is an account of the first distress and war cry, (to appropriate an expression of the Salvation Army), and while the workers in Science may take a considerable time to make observations and investigate the “reasons for things,” the underlying claims herein stated will, it is believed, ultimately be established as fundamental facts of both Hygiene and Physiology.

The psychic factor in digestion is even more important than originally claimed by the author, and fully accounts for the strength attained by the Christian Science movement.

In the “A.B.-Z. of Our Own Nutrition” are reprinted, for recent scientific reports, in addition to the papers of Dr. Van Someren and Professor Chittenden, before mentioned, articles and lectures by Dr. Professor Pawlow, the great Russian physiologist and one of the Board of Assessors in the International Nutrition Investigation, described in the “A.B.-Z.,” (reprinted from the fine English Translation by Dr. W. H. Thompson, of Trinity College, Dublin; English publishers, Griffin & Co.; American publishers, Lippincott & Co.), on the mental influence over the salivary, gastric, and intestinal secretions. Also, nearly an hundred pages of most virile, readable, and important “Observations on Mastication,” by Dr. Harry Campbell, M.D., F.R.C.P., of the North-west London Hospital; reprinted by courteous permission of the author and of the editor of the Lancet. Also, a description of the digestive process in animals as seen by aid of the Röntgen, or X-Ray; a most readable account of the infinite patience and application of Dr. W. B. Cannon, of the Harvard Medical School, devoted to learning the “reasons for things” done in the closed and secret laboratory of the stomach and intestines.

The above is a necessary advertisement of another volume in the A.B.C. Life Series; because the details of this particular attempt to reduce the philosophy of every-day life to profitable simples is linked-up in several volumes developed in the course of study of the subject for location of the germinal causes.

“Menticulture” was the first of the series and relates to the individual. “Happiness” came next and located the chief enemy of happiness in Fearthought, the unprofitable element of forethought. “That Last Waif” treated the question as related to the Social Whole, children in particular, and recommended Social Quarantine; by extension of infant education to the extreme of allowing no child to escape educational care. This present treatise deals with the first requirement of such infantile care and education, right feeding.

DR. KELLOGG’S APPRECIATION

The great Battle Creek Sanitarium, under the inspiration and direction of Dr. J. H. Kellogg, has grown to enormous proportions in thirty-seven years. It began with one patient in a two-storey frame house in a country village, and has been largely influential in creating the present proud distinction of Battle Creek, Michigan, with its millions upon millions of invested industrial capital.

The “cure” is based upon the establishment in the patient of right nutrition, right functioning of the bodily organs and secretions, and thereby assisting Nature to perform the cure in a natural manner. Pure foods and other conditions of right nutrition have been the particular study of the institution staff, and large and finely furnished chemical and bacteriological laboratories have been installed for the study of nutrition in a scientific manner.

The Battle Creek Sanitarium is a purely humanitarian and philanthropic institution. By perpetual charter, all of the profits of the concern in all of its ramifications are dedicated to the extension of the American Medical Missionary Cause, and there have been already established more than sixty branches of the parent institution in different parts of the world, principally in or near the chief cities of America, and all are occupied with saving and regenerating the physical body of the sick as a foundation for possible moral awakening and spiritual cultivation.

The work done by these humanitarian institutions is most practical, and the best evidence of the practicality is their growth. Patients are charged what they can conveniently pay, but none who need are refused attention. Branches are made self-supporting as soon as possible, but are first nurtured by the parent sanitarium. There are some hundreds of physicians, nurses, and other attachés of the different institutions, and these are enthusiasts in the humanitarian work, taking as wages only what they need for most economical support, “a mere pittance,” and deriving their chief compensation from satisfaction gained in the service. All in all, it is an expression of inspirational altruism worthy of the example of the Good Samaritan and a practical demonstration of the Sermon on the Mount.

The special attention of the writer was called to the work of the Battle Creek Sanitarium organisation by an American banker, Edwin C. Nichols, Esquire, in London, at the time of the last Coronation. The banker was conversant with the growth and methods of the Sanitarium, and had seen the result of its missionary and sanitary work. He exacted a promise from the writer to visit Battle Creek on his first opportunity, and Mr. Nichols has our everlasting gratitude for leading us to a more intimate acquaintance with so splendid an illustration of humanitarian possibilities when properly directed. It is not alone the great Sanitarium and its hospitals, and clinics, and shelters, and refuges, and baths, and reading-rooms, that are doing the greatest possible good work, in demonstrating their effective Christianity; but it is the private waif-family of Dr. and Mrs. Kellogg which shows what neglected children are capable of when given a chance, and which appeals to the author especially as giving support to his ideal of a possible effective Social Quarantine as presented in his book, “That Last Waif.” Twenty-four neglected and sick children of unfortunate parents have been rescued from an almost hopeless condition, and have been adopted into the best of surroundings and culture, all promising to become splendid wealth-productive citizens and ornaments to society.

For more than a year Dr. Kellogg and his staff of earnest workers have been testing the suggestions offered in “Glutton or Epicure,” and in the treatise of Dr. Van Someren, and appreciation of these suggestions and the work that has since been done to stimulate interest in the question in high scientific circles will be found in some extracts from Dr. Kellogg’s letters which the author has received permission to print herewith.

“Battle Creek, Mich., Nov. 26, 1902.

Dear Mr. Fletcher:

“I have your kind note of November 20th. Thank you very much for your appreciative words. Your visit here was a great inspiration to all of us. It is not often we find a man who enters into the things which we love so heartily as you have done. The thing that interested us especially was the fact that you are the founder of a new and wonderful movement, which is bound to do far more for the advancement of the principles for which we are working than all that we have done or anything we can do. I shall await with great interest the development of your work and shall expect to receive great light from your efforts. We are all in training to find our reflexes, and are expecting to make a great deal out of this.”

“Battle Creek, Mich., Dec. 21, 1902.

“My dear Friend:

“I have received the beautiful book which you sent me, ‘That Last Waif, or Social Quarantine.’ It is a charming volume. I devoured it eagerly, and I find myself in the position of an eager disciple sitting at the feet of a master. Your ideas of social regeneration strike deeper than those of any other modern author, and I shall be glad to coöperate with you in any way possible in promulgating these principles. You have made your book talk in a most impressive way. From cover to cover it is simply admirable and must do a world of good. I shall write a little notice of it for my journal, Good Health.

“Again thanking you for this interesting volume, I remain,

“Most sincerely and respectfully

yours,

“J. H. Kellogg.”

“Battle Creek, Mich., Jan. 22, 1903.

“Dear Friend:

“I have shamefully neglected you. I want to assure you how much I appreciate your encouraging notes. I read them to my colleagues, and they were so much affected that tears came into their eyes. I assure you we feel that you are indeed a brother to us in our work, and that God has providentially sent you to be a friend to us and to the principles which we represent.

“I had a letter from Dr. Haig a few days ago in which he mentioned you and your work, and said he was much interested in it. Dr. Haig, you know, has done a great deal in calling attention to uric acid in meats and other foods. His work has not all been accepted by great laboratory men, but Dr. Hall, of Owen’s Medical College in Manchester, has recently reinforced his results. I have at different times repeated his experiments with interesting results.

“I assure you we shall be glad to receive any suggestions from any scientific authority who may visit us, and if there is any part of our work which can be improved, we shall be glad to put it there as soon as our attention is called to it.

“Again thanking you for your kindly interest in our work, I remain,

“Most sincerely yours,

“J. H. Kellogg.”

“Battle Creek, Mich., Jan. 22, 1903.

“My dear Friend:

“I have yours of January 29th. I am much interested in what you write about your demonstration at New Haven. I want to give the widest publicity possible to your work. I find great good in it. I am talking to my patients continually about it. I know from my experience that you are right. For many years I have required my patients to give special attention to chewing, and have made it a written prescription for each patient to chew a saucerful of dry granose flakes at the beginning of each meal. I have seen great good from this method.

“With kindest regards, I remain, as ever,

“Most sincerely yours,

“J. H. Kellogg.”

“Battle Creek, Mich., Jan. 22, 1903.

“Dear Friend:

“I am exceedingly interested in the facts which you communicate, especially Dr. Anderson’s report. It is quite remarkable. I am verifying the same ideas in my own personal experience. I am confident you have discovered a great and important principle and I shall watch with interest future developments. I am going to get our students interested in it. If you feel disposed to do so, I shall be glad to have you make out a little line of experiments which will tally with the experiments which you have been conducting, so the results may be compared.

“I have in hand a translation of Cornaro’s work which I have been thinking of publishing. It occurred to me that perhaps you would be able to write a little chapter for this work, or an introduction. I am going to get it out in nice shape, and I trust it may be the means of doing good in inclining those who read it toward a simpler life. I am greatly interested in the ideas which you present in your various books.

“I hope you will have a safe journey to Italy and back.

“I remain, as ever,

“Very sincerely and respectfully

yours,

“J. H. Kellogg.”

“Battle Creek, Mich., Jan. 22, 1903.

“My dear Mr. Fletcher:

“I have yours of March 19th. I thank you very much for promising to write an introduction for the edition of Luigi Cornaro’s life. You are just the man to do it. I propose to get the book out in neat, tasty shape. Shall be glad to have suggestions from you on this point. The manager of a large denominational publishing house in Chicago is interested and wants to publish it with us. He has promised to help about the artistic features.

“As regards our medical college, I ought to have told you that we are incorporated in the State of Illinois. Our medical school is really legally located in Chicago. We always have one or more classes down there for dissection, clinical work, and doing dispensary and missionary work in the city. Our school is officially recognised. Our diplomas are recognised in this country and in most foreign countries; our diplomas are recognised, in fact, in all countries which recognise American diplomas. The work done in our school is recognised by the best schools. Jefferson accepts students from our third year into their fourth, the graduating year, without examination. Kings College in Kingston, Canada, does the same; also Trinity College in Toronto, and other leading schools in this country. Our College is a member of the American Medical Association along with Bellevue, University of Pennsylvania, University of Michigan, Rush Medical College, and other leading schools. We have placed our standard high so that no one could object to the reform features of our work on account of incompetency. Our students are admitted to practice in New York, having passed the examinations of the State Board. Our best reason for believing that our diplomas are recognised everywhere is because of students from the College having passed the examinations in nearly every State. One of our students recently graduated from the University of Dublin after having spent a year there, as they require five years instead of four years as with us.

“Your experiments are surpassingly interesting. Your performance with Dr. Anderson was phenomenal. I confess you are a physiological puzzle. If chewing accomplishes these wonderful things for you, it is certainly worth the while. I am training myself from day to day to masticate my food more and more thoroughly and I confess there is greater good in it than I ever imagined.

“I am sending you a little box of foods that I think you will like, especially the protose roast, the gluten biscuit, and the chocolates.

“I would like to get hold of a list of your books; I want to put them into the hands of our students to read. Kindly give me a list of the names and the publishers and I will esteem it a favour.

“I might have said further in reference to our College that it is listed by the New York Board of Regents as well as by the Illinois State Board of Health. We are going to make considerable improvement in our school the next year. We are trying to put up a new building. We need $100,000 very much, as our work has no endowment and it requires very great sacrifice and most strenuous effort to keep it going. Our teachers work for a mere pittance and our students are compelled to save and economise in every way to get through. Nearly all of them have to pay their way in work of some sort.

“By the way, I am taking liberty to send you with this, copies of some little booklets which I have just gotten out in reference to our work.

“I am, as ever,

“Your friend,

“J. H. Kellogg.”

“Battle Creek, Mich., Jan. 22, 1903.

“My dear Friend:

“I have your kind note of June 21st. I am happy to be remembered by you tho I have neglected writing you. I was afraid my letter would not find you on your journeys.

“We are chewing hard out here at Battle Creek, chewing more every day. We are continually thinking and talking of you and the wonderful reform you set going. We have gotten up a little ‘chewing song’ which we sing to the patients. It is only doggerel but it helps to keep the idea before our people. We dedicated it to you and I am going to send you a copy of it as soon as the printers get it ready. If you feel too much disgraced I will take your name off.

“That little book on ‘Cornaro’ is not out yet. We have been waiting for the introduction from you. We can wait as much longer as is necessary, as you are the man to furnish this introduction.

“I hope you will come West some time this summer so you can drop in and see us in our new building. We are not quite in perfect running order yet, but we shall soon be fixed in good shape and will be delighted to have you with us. You have helped us greatly in calling our attention to the great importance of chewing. We had known it for a long time but had not practised it. You demonstrated the thing in such a graphic way that the whole world is constrained to listen.

“Thanking you for your kind note,

“I remain, very sincerely yours,

“J. H. Kellogg.”

“Battle Creek, Mich., Jan. 22, 1903.

“My dear Mr. Fletcher:

“I have your kind favour of July 14. You are doing me altogether too much honour. I am only a plodding, humble doctor, and have never had any opportunity to do any great thing, because of the limits of my abilities, and because I have not the opportunity to devote my energies to any one special thing; but have so many things to do that I can do nothing very well.

“I remember Dr. Krauss very well. He has for some years been assistant to Prof. Winternitz, the Professor of Nerve Diseases in the Medical Department of the Royal and Imperial University of Austria. He seemed a very able physician and a delightful gentleman. I was very glad to meet him.

“I have already sent you a copy of a little booklet entitled ‘The Building of a Temple of Health.’

“We will be most happy to have a visit from you. I would like to know about what time you are coming, and I will endeavour to be here. I have a call to give an address at Chautauqua, N. Y., early in August, and if I do not know when you will be here, I might possibly be away, which I should consider a great misfortune.

“We have nothing here, I am sure, which will be new to scientific men, and I apprehend that they will have a very different opinion of our work than you have.

“I have a little book which I think I have not sent you, entitled ‘The Living Temple.’ I will send a copy to you; also a copy of the ‘Chewing Song,’ which is now out. It is nothing but a cheap thing, intended only for my own little folks; but it got out, and several people wanted it, so I have allowed it to be put in print. The purpose was, of course, simply to impress the chewing idea. Of course you are well, as you are apt to be well by chewing well.

“By the way, I met a disciple of yours a day or two ago. He was Senator Burrows, from Kalamazoo. He called with his wife and some other ladies, and Mr. Rose, the chief clerk of the U. S. Senate, to make us a little visit. I had a very delightful chat with them. On remarking to the Senator that he did not look any older than when I saw him last, but seemed to be very well, he told me he was in perfect health, and he expected to live for ever. He had recently gotten hold of something that was doing him so much good that he believed he should never be sick. I begged to know his secret, and found it was chewing. I asked him how he discovered it, and he told me he had learned it from your delightful book. You are certainly promoting the most important hygienic reform which has been brought forward in modern times. When you visit us again, you will see in our dining-room of our new building more Horace Fletcher disciples, and more hard chewers than you ever saw together in one place in your life before. Our doctors and helpers are taking hold of it with great enthusiasm, and I trust we shall be able to render you some good service in promoting this good idea, for which you certainly deserve the gratitude of the whole world.

“Hoping to have the pleasure of a visit from you soon, I remain, as ever,

“Yours most sincerely and respectfully,

“J. H. Kellogg.”

“Battle Creek, Mich., Jan. 22, 1903.

“Dear Friend:

“Your kind notes of August 7th and 11th received. I have asked the Publishing Department to open an account with you and send you everything you order promptly at publisher’s discount.

“‘The Living Temple’ is published for the benefit of the Sanitarium. Everything received from it goes toward paying for the new building. The cost of printing, paper, and binding is paid for by contributions, so all the money received goes toward the building fund for the Sanitarium. I hope by this and other means to get the building paid for before I die.

“I think your chewing reform is of more importance to the world than you realise. You must have a great fund of good cheer with you; doubtless because you chew! I told our patients here that I had heard from you that King Edward was chewing. It interested and amused them very greatly. The idea of ‘munching parties’ is a good one.

“As ever,

“Your friend,

“J. H. Kellogg.”

“Battle Creek, Mich., Jan. 22, 1903.

“Dear Mr. Fletcher:

“I have yours of August 20th with the list of persons to whom you desire to have ‘The Living Temple’ sent. The books are already sent together with a little note calling attention to them.

“Your continued courtesies are putting us under obligations which we can never repay.

“There are a lot of devils of different sorts to be cast out, and I am sure the dyspeptic devil is about the worst and the meanest of them all.

“A quartette sang the ‘Chewing Song’ just before my lecture in the parlour last evening. The great parlour was filled to its utmost capacity. The people cheered heartily, not at the singing nor the song, but the sentiment. I took occasion to tell them I thought Mr. Horace Fletcher, in inaugurating the chewing reform, had done more to help suffering humanity than any other man of the present generation, and that I felt very much mortified that we had neglected this important matter to such an extent here that you had to come to the Sanitarium and be a missionary of good health and urge this important matter upon our attention. I feel that we are all greatly indebted to you, and seem to be getting continually more and more into your debt, and I do not know any way to discharge the obligation; but if any accident should ever happen to you so you get ill, it will certainly be a delight to us to have the opportunity to minister to you if you will permit us so to do.

“I am glad you have postponed your visit until October, as by that time we shall have many things in better working order, and our medical class will be here. I want to have our medical students meet you.

“I told Mr. Nichols the other day you were coming to visit us. He was greatly delighted to hear this. He feels as I do that the work which you have inaugurated is the most important movement which has been started in modern times.

“I remain, as ever,

“Fraternally yours,

“J. H. Kellogg.”

“Battle Creek, Mich., Jan. 22, 1903.

“Dear Friend:

“I have your kind note of the 23d inst. I am sure that one of my letters to you has been lost. I wrote promptly telling you that you were at liberty to use anything I have written you respecting your work.

“I am more and more enthusiastic respecting the value of thorough chewing. I have read with great interest Dr. Harry Campbell’s articles, and am republishing in Modern Medicine a large part of what he has written.

“I have been thinking whether I might dare ask permission from you to publish your article ‘What Sense’ as a tract. Possibly it is already printed in that way. I would like to circulate it widely among my patients, and our nurses and doctors. I am doing my best to get them all to chewing, and have had great benefit myself from thorough mastication.

“Our Medical School has just begun again, and I have one nice class of sixteen students who are going to devote themselves to the study of applied physiology, and all of them will experiment on the effects of thorough mastication in relation to the quantity of food; also in relation to the quantity of proteids. If you would like the details of the results of the experiments, I will give them to you later.

“By the way, if you have any written or printed outline of data which you think it desirable to collect, I will be glad to have it as a help to us in researches of this sort. We have prepared our laboratory to do almost anything that needs to be done, and we have a whole lot of enthusiastic young men and women who will enter into this thing with great zeal, and we will be glad to coöperate with you thoroughly as I feel that you have introduced a line of research and investigation which is of immense importance. I have read with great interest Prof. Chittenden’s article in the Popular Science Monthly, and I can but feel that you are a heaven-sent missionary to the world in this matter of diet reform.

“I remain,

“As ever your friend,

“J. H. Kellogg.”

“P. S.—I have for many years given a good deal of attention to the matter of mastication. It has been my regular prescription for all my patients for many years to eat at the beginning of each meal some Granose Flakes. The purpose of this was to secure increased activity of the salivary glands, and to encourage the habit of mastication. I have found immense benefit from this practice.

“I appreciate exceedingly all the good things you are sending me. What a delightful time you must have had in the Adirondacks! I have never had such a pleasure in my life, as I have had my nose continually on the grindstone at work since I was ten years of age, with no vacations at all. It is a remarkable spectacle that these great men, these learned professors and scientists, and army medical men, should be coöperating so enthusiastically with a layman to learn the true philosophy of life; but it has always been so. The great discoveries have not been made by great scientists and great doctors, but by men whose minds were above the bias of prescribed education, and who were able to learn from the great book of nature, which is the book of God.

“When you come again I hope you will have time to stay with us a little while so we can have some good chats. I would like to sit down and go into the heart of things with you, when I think we should find our ideas running very close together. We shall expect to see you next month. I have to be away for a few days sometime during the month, so I hope you will let me know a little while before you come about what time to expect you.

“J. H. K.”

EXTRACTS FROM DR. EDWARD HOOKER DEWEY

(At the first writing Dr. Dewey had had the method of treating food commented on in his letters under trial for three years; it having been communicated to him by the author among the first.)

“Meadville, Penn., Nov. 17th, 1901.

“My dear Mr. Fletcher: